Directed by David Cronenberg, starring Jeff Goldblum and Gina Davis

From Howard Shore’s epic soundtrack to Jeff Goldblum’s overwhelming performance of power and deep sadness, David Cronenberg’s “The Fly” is one of horror genre’s finest achievements. It’s a film that’s as intense as “The Exorcist,” and every bit as terrifying.

Of course, the whole thing wouldn’t work if Goldblum didn’t deliver.

He does, and far more. Released in 1986, the moment Goldblum’s Seth Brundle explodes on screen, it’s impossible to take your eyes off him. This is a performance that hits every nerve. Goldblum commands as much sympathy and tragedy, as he does fear and dread. In fact the film overall can easily be seen as a romantic tragedy, with Gina Davis doing her damndest to keep up a pace that’s exhausting. In a good way.

Quickly, the plot. It’s the story of Seth Brundle, genius scientist who has discovered what will change the world. When he meets Davis’ eager reporter, Veronica Quaife, he tells her that every other scientist who has said the same thing, is a liar. That he’s not. The moment Brundle takes Quaife to his clandestine laboratory she knows the scientist is speaking the truth, for Brundle has invented teleportation, which he proves to her by teleporting one of her stockings from one “telepod” to another. The pods themselves look insect in nature, giving the opening shots some of the most effective foreshadowing in cinema.

But this film is about the performance and the emotional jolt that’s permeant for the audience. If you’ve never seen it, nothing will prepare you for it. If you have, then nothing about it will it leave you.

What makes Goldblum’s Brundle so remarkable is Brundle’s transformation. Not just because of what happens to him when he teleports himself and a fly happens to be in one of the pods, but the emotional and intellectual transformation of an elite scientist to the desperation of surviving a reality where, medically, nothing that can save him. Brundle uses every piece of his mind, body, and spirt, to stay alive as long as possible.

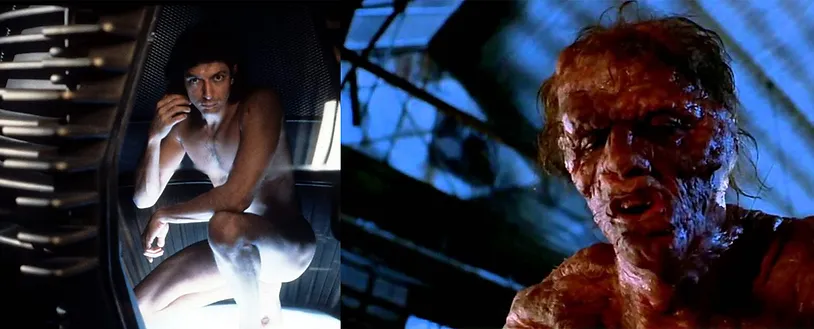

It’s a transformation that Goldblum manages so effectively that the three phases he goes though are so convincing it’s like watching three different characters. There is the confident, yet insecure, scientist who knows his talent and ingenuity are matchless. There is the infected scientist who uses all the tools of science, physics, and medicine, to endlessly seek a solution. Finally, there is the fused monster of insect and human where madness and anger have completely taken over anything Brundle once resembled, body and mind.

Perhaps the greatest scene takes place when Brundle still has a few shreds of humanity left and gives the Insect Politics lecture to Quaife, while she knows her love for him has been shattered by science turned shockingly unhinged. “Have you ever heard of insect politics?” He asks. “Neither have I,” he continues as Davis is absolutely horrified. “Insects don’t have politics. They’re very brutal. No compassion. No compromise. We can’t trust the insect. I’d like to become the very first insect politician. I’d like to…but I’m afraid that –” Davis interrupts with utter sorrow and confusion, having no idea what he’s talking about. He continues, “I’m saying I’m an insect who dreamt you as a man, and loved you, but now the dream is over, and the insect is awake. I’m saying I’ll hurt you if you stay.”

It is unimaginable that any other actor other than Goldblum could create such a preposterous moment and turn it into a scene of astonishing grace and melancholy. It is here that we are cheering for the monster’s survival, for some last moment of hope that a magical cure will appear. Davis’ reaction is so filled with anguish that we suffer right along with her all the way to the tragic ending where the fused insect beast begs to be destroyed by taking the barrel of a shotgun held by Quaife’s boss (played by John Getz with stark cynicism as well as gleeful awe), and placing it directly to the awful mess’s head. By this time, because of the many teleportation experiments Brundle attempts to find a solution to survive, what’s become of him is a fusion of insect, human, and massive fragments of telepod metal. Nothing quite like it has ever been filmed since.

Cronenberg’s “The Fly” is a grand achievement in horror. What he and Goldblum created is what every element of horror strives to become: a story that examines the depths of the human condition when presented with the impossible. It’s the reason horror can be so glorious.

Leave a Reply